BALTIMORE — An experimental drug is bringing science one step closer to curing Type 1 diabetes. Scientists at Johns Hopkins Medicine are reporting that an experimental monoclonal antibody drug prevents and reverses the condition in mice. In some cases, it even extended the animals’ lifespans.

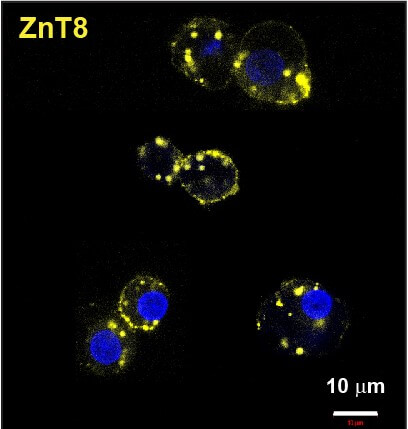

The drug is called mAb43 and is quite unique, according to the research team. If you have Type 1 diabetes, an autoimmune condition, your pancreas makes little to no insulin. This drug works by directly targeting insulin-making beta cells in the pancreas and shielding them from attack by the body’s wayward immune cells.

Such a level of specificity might allow for long-term use in humans with few side-effects, according to the study published in Diabetes. Monoclonal antibodies are made by cloning an animal cell line.

The findings help build a pathway for a new drug for Type 1 diabetes, which could be life-changing for close to two million American children and adults who have the currently incurable condition. It differs from Type 2 diabetes, where the pancreas makes some insulin but not enough to fulfill the body’s needs.

“People with Type 1 diabetes face lifelong injections of insulin and many complications, including stroke and eyesight problems if the condition is not managed properly,” says Dax Fu, Ph.D., associate professor of physiology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and leader of the research team, in a media release.

Fu adds that mAb43 binds to a small protein on the surface of beta cells in order to act as a shield to “hide” them from immune system attacks. Since a mouse version of the monoclonal antibody was used for this study, a humanized version is still necessary in before this drug can reach patients.

The trial included 64 non-obese mice bred to develop Type 1 diabetes. They were given a weekly dose of mAb43 intravenously starting at 10 weeks-old. After 35 weeks, none of the mice were diabetic. One of the mice went on to develop diabetes for a brief period of time but ultimately recovered at 35 weeks. Even before the antibody was administered, that mouse was showing early signs of the disease.

In five of the same type of diabetes-prone mice, the researchers delayed giving weekly mAb43 doses until they were 14 weeks-old, and then they continued giving them the treatment until week 75. One of the five developed diabetes, but no adverse events were noted. When mAb43 was administered early on, the mice lived for the entire 75-week monitoring period. The control group that didn’t receive the doses lived shorter lives, between 18 and 40 weeks.

“mAb43 in combination with insulin therapy may have the potential to gradually reduce insulin use while beta cells regenerate, ultimately eliminating the need to use insulin supplementation for glycemic control,” says postdoctoral fellow Devi Kasinathan.

Another monoclonal antibody drug called teplizumab was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2022. Teplizumab works by binding to T white blood cells, rendering them less harmful to insulin-producing beta cells. It has been shown to delay the onset of clinical Type 1 diabetes by nearly two years. This gives young kids, who are the main group developing the disease, time to learn how to manage their condition with diet and insulin regimens.

“It’s possible that mAb43 could be used for longer than teplizumab and delay diabetes onset for a much longer time, potentially for as long as it’s administered,” says Fu.

“In an ongoing effort, we aim to develop a humanized version of the antibody and conduct clinical trials to test its ability to prevent Type 1 diabetes, and to learn whether it has any off-target side effects,” concludes researcher Zheng Guo.