After helping my childhood friend, Cloud, through a reality-bending experience to reclaim his identity, I listen as he apologizes for his worst actions and explains to a room full of people why he misled everyone. Yes, his mind was under the influence of an invasive presence, but this confession comes from a place of vulnerability, one where he’s owning his own actions. He confesses to being “ashamed of being so weak” to the point that he “created an illusion.” When he says he “can’t remain trapped in an illusion any more,” and that he’s “going to live […] without pretending,” I feel inspired not only to defeat the evil we are facing, but to live my own life without pretending too. We all walk back to the cockpit of the airship called the Highwind, headed north to face our greatest fears with honesty and resolve in who we are, together.

Final Fantasy VII arrived on the original PlayStation on January 31, 1997 and it swiftly became a worldwide, cultural gaming phenomenon. In the more than two-and-a-half decades since, FF7’s world, characters, and soundtrack, not to mention the thrill of playing through its innovative, adventurous, and varied quest, have remained fresh and inspiring in the minds of countless gamers—especially for those of us who played it at an impressionable age in the late ‘90s.

As a kid, I experienced FF7 as a three-disc epic on a massive, glowing CRT screen that would loom over me for hours at a time, a disc spinning away under the plastic lid of my gray PlayStation with a colorful PSM sticker slapped on it. Final Fantasy VII pulled me in with a gravitational force unlike anything before, and few works of art have come close to hitting me in the same way.

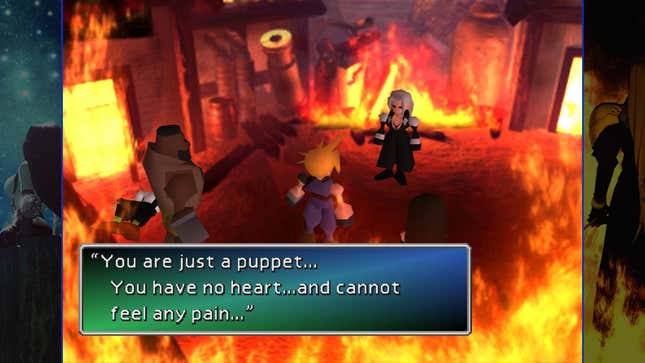

But is that all just nostalgia talking? Final Fantasy VII, with its narrative that questions what parts of one’s memory can be trusted, also invites us to question our own recollections of playing it, and see how our opinion of it differs upon returning to it years later. Final Fantasy VII is a game about so, so much. It deals in massive, overwhelming concepts like unchecked corporate power and greed leading to ecological collapse and violence inflicted on the less fortunate, but is also intimate enough to be filled with tender and delicate moments such as someone longing to confess their love to a friend, only to fail and struggle to find the courage and the right words.

FF7 features heroism at its most inspiring and villainy at its most terrifying. It uses the genres of science fiction and fantasy to stretch its story across a mind-bending cosmic reality with characters who are not only saddled with saving the world, but who must also navigate deeply human and relatable burdens: the precious coexistence of friendship and love, having your dreams taken from you, the loss of dear friends and family, of finding family, of finding yourself. Atop these burdens soars a spirit that reminds us that no matter the odds, we must strive to fight for and be something better than what the worst of reality has to offer.

Many may love Final Fantasy VII because it was a special game to them at a young age. Such a relationship ought not to be dismissed. Nostalgia may provide context as to why we do or don’t like certain things, and while it should sometimes be questioned, it needn’t be discounted. Nostalgia is a human act of cataloging our sense of self, our minds and bodies, with how we move through time and space, taking note of who and what was around us. As I’ve revisited FF7 with my first full complete playthrough in many years, I’ve sought to be aware of my nostalgic relationship with it as best I can. And after once again winning its climactic battle and watching its beautifully mysterious and hopeful post-credits scene, I remain convinced that FF7 more than earned the admiration it received in 1997.

Read More: So You Want To Play The Original Final Fantasy VII?

So much has changed since 1997. Where once I clutched a wired gamepad and sat in front of a massive, boxy television, today the game follows me out into the world. Like a reissue of a classic fantasy novel, it gets tossed in and out of my bag on my way to work; I play it while waiting in doctor’s offices, while sitting in the park, on the train, in cabs, on buses. And yet, Final Fantasy VII itself remains much the same: It’s a rewarding RPG with a flexible and engaging combat system, unlabeled secrets to unearth in a fascinating fantasy world, and stories of identity, connection, and loss that make me cry every single time.

FF7’s opening is everything

FF7 opens with swirling stars against the endless black of space. Then, a close-up of a character who would become just one member of a timeless cast of recognizable faces. The camera spends some time with her before pulling out through a bustling city street to take us further into the air, where we look down on an impressive and ominous megalopolis drenched in shades of black and green. Proud and audacious melodies soar from the speakers, the grinding wheels of a train cut in and out of the scene, and we zoom in to follow said train pulling into a station.

From there, it’s all narrative propulsion, a rushing train setting the tone for the single-minded focus of the game’s opening section. A rag-tag bunch of eco-terrorists, a “Bombing Mission” on a reactor (accompanied by an unforgettable music track of the same name), and an immediately iconic protagonist, spiky-haired and wielding a massive sword. It’s an opening for the ages.

A few moments later we’re given the choice to name our character, or roll with his given name: Cloud. Another character, Barret, who’s quick to swear and doesn’t shy from giving bold speeches, tells us that the planet is dying. The “life blood” of the planet is being harvested by our antagonist, Shinra, and their “weird machines.” Our protagonist can’t be bothered with these motivations. “I’m not here for a lecture,” Cloud says before he and Barret push through the labyrinth of concrete, metal, pipes, billowing smoke, and flashing lights toward their explosive goal.

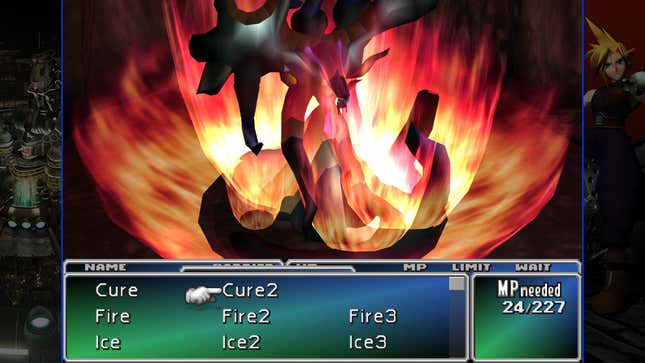

This direct urgency and linear scripting takes you through the first few hours of FF7. Aside from some opportunities to explore certain areas, and a few moments of down time, FF7’s early moments are on rails, barreling toward the goal of trying to sabotage Shinra as an act of direct environmental action. As a game, this tight pacing gives us the space to learn FF7’s RPG system without being too overwhelmed by the urge to explore. And it’s an excellent RPG system that lets the player modularly construct classes by way of slotting spells into slots via magical orbs known as materia.

Importantly, the narrative linearity gives you time to connect with the central characters: Cloud, Barret, Tifa, and Aerith. You come to understand how they each relate to the antagonistic corporate force that literally looms over its subjects. The city of Midgar is divided into two halves, one that sits atop a massive circular plate adorned with luxury and spectacle, and the other that lies below it, filled with wreckage and poverty.

The structure of FF7’s early moments run parallel to the story it’s telling. There’s even a literal reference to train rails early on from Cloud:

I know…no one lives in the slums because they want to. It’s like this train. It can’t run anywhere except where its rails take it.

Though you can’t freely roam Midgar, the city never fails to feel massive. Much of this has to do with the clear attention to detail poured into the fixed, pre-rendered backgrounds: intricate machinery, the sometimes messy yet comfy and lived-in feel of the homes of its citizens, seamy town squares and storefronts. By today’s standards, these backgrounds are notably low-res, with objects that are sometimes hard to discern, but they’re each works of art in their own way. There’s a clear artistic perspective here. This isn’t just empty space to explore, like what many modern, much larger open-world games typically fill their spaces with. The placement of each object in these scenes feels intentional.

After many battles below the surface of the streets of Midgar, we’re brought to the top. Raiding Shinra HQ is our chance to strike back after witnessing the company destroy countless lives…and that’s where FF7 reveals its first twist: Yes, the planet is dying, but the threat is far greater and far stranger than our heroes believed.

And then…the world

After the exhilarating raid on Shinra HQ, FF7 settles into a rhythm that those who played the first six Final Fantasy titles will know well: the wide, roaming spaces of the overworld.

By holding this space back from you early on, FF7’s deliverance of the planet hits with an impressive, perhaps even intimidating, spaciousness. It’s a direct contrast to the claustrophobic nature of Midgar. It serves as a welcome change of pace from the game’s opening. However, although it feels very wide and open, FF7’s story and world still have a relatively linear path, just one with wider spaces to navigate between story points and a few more opportunities for diversions.

Yet the planet of FF7 always feels massive. The structure of when and how it shows you this world doesn’t just make for a satisfyingly paced story, it harmonizes with FF7’s tale about saving the world from destruction.

FF7’s story runs parallel with its structure as a video game. Everything gets larger as you’re given more space to explore. The antagonist gets swapped from the Shinra company to the more existential and profound threat of Sephiroth and his mother, Jenova. Shinra’s role in the creation of Sephiroth always remains present, but the goal remains the same: Save the planet. And you’ll see nearly all of that planet. You’ll walk, drive, and eventually fly across its entire surface. FF7 features a wide array of locales, people, and narrative twists and turns, set to a timeless soundtrack that knows how to make use of recurring melodies and sharp contrasts in genre to set an appropriate tone for each scene. It all makes this world feel larger, and your journey through it more varied and epic, than just about any modern open-world game can achieve.

True, FF7 does feel dated by today’s standards in some key ways. Fast travel points, quest markers and objectives, auto-save, none of that’s here. You have to physically go to the location in mind, actively choose to save, and remember where the next objective is. It can be a little rough to go back to a time when such quality-of-life features weren’t standard, and there were times that I wished I could double-check my objective in a quest log or warp from, say, Wutai to Junon by selecting icons on a map. But FF7 delivers such a memorable story and such unforgettable characters over its roughly 40-hour campaign that these are minor discomforts at best—and in 1997, there really wasn’t yet a model for an alternative to this structure, anyway.

FF7 was full of technical marvels for its era, to be sure. But upon revisiting FF7 today, I’m convinced that the elements we today consider so dated, things like its text-only dialogue and, yes, its blocky, square-fisted characters, actually contribute to its ability to occupy space in the mind of so many players, and to remain there, puzzling and cherished, for decades..

Text boxes, signature blockiness, and low-fidelity charm

In Brian Eno’s A Year With Swollen Appendices, the storied musician and record producer discusses the essence of “ugly” and even “nasty” elements of older forms of media. He says:

Whatever you now find weird, ugly, uncomfortable and nasty about a new medium will surely become its signature. CD distortion, the jitteriness of digital video, the crap sound of 8-bit — all of these will be cherished and emulated as soon as they can be avoided. It’s the sound of failure: So much modern art is the sound of things going out of control, of a medium pushing to its limits and breaking apart. The distorted guitar sound is the sound of something too loud for the medium supposed to carry it. The blues singer with the cracked voice is the sound of an emotional cry too powerful for the throat that releases it. The excitement of grainy film, of bleached-out black and white, is the excitement of witnessing events too momentous for the medium assigned to record them.

It’s that last line which really connects this sentiment to Final Fantasy VII for me. FF7’s blocky polygonal characters, its low-resolution pre-rendered backgrounds forever stuck in a non-cinematic aspect ratio, the rigid timbre of its soundtrack manage to communicate, as Kotaku’s managing editor Carolyn Petit once put it, “hand-crafted charm.”

Like seeing brushstrokes in a painting, FF7 looks and feels like it was made by real people aiming to capture the collective artistic frequency that everyone working on this game was tuned into, using the tools and technology they had available to them at the time. To borrow from Eno, to be excited about FF7’s 1997 presentation is to experience “the excitement of witnessing events too momentous for the medium assigned to record them.” Playing FF7 is like listening to a record where you can hear not just the song, but also the musicians in the rooms and the spaces where they recorded their parts.

The polygonal characters of FF7 only have so many animations. Over the course of 40 hours, you’ll have seen them all used for a wide variety of different expressions. Some are unique to certain characters: Cloud’s “shrug,” or Yuffie’s speedy air punches. And some are hilarious, such as Red XIII literally crossing his arms like a person during a late-game showdown with an antagonist.

But there’s always character and personality present in these animations, like Red XIII’s adorable and labored crawl under the hot sun of Costa del Sol after he remarks that the “heat is drying my nose.” The same is true of the soundtrack, which chose to eschew the PlayStation’s capability of playing recorded, “Red Book,” CD-quality audio with sequenced notes and samples. It too is rigid, yet its use of melody and song structure, and knowing when to pivot genres, paints the soundscape of a world and its people. That’s true whether we’re talking about delicate and atmospheric tracks like “Lifestream” or “Words Drowned by Fireworks,” or the pounding progressive heavy metal vibes of “Fight On!” or “Birth of a God.”

Every movement, line of dialogue, and musical beat feels hand-picked, deliberate, and engaging. FF7 sometimes feels like watching a work of theater on stage, with actors moving around an intricately and intentionally designed set, meant to draw and keep our attention as players, before wowing us with what were at the time wildly impressive graphical showcases in its “FMV” cutscenes, and allowing us the urgency to do battle against the world’s worst villains.

Don’t dismiss the English version!

As you may know, Final Fantasy VII’s English version had a rushed and rough translation from the original Japanese. This resulted in more than a few odd sentences and word choices and some now-iconic grammatical errors.

Modern versions of FF7 have largely cleaned this up, but this rushed translation has contributed to a certain character unique to the English version. Also, the English script is more than capable of delivering laughs and tears, and communicating the nuances of FF7’s many twists and turns. If you can read Japanese, you probably should play the game in its original language. But you’ll still have a wonderful time with the English version.

Where the limits of FF7’s ‘90s tech fall short, that’s where the player’s imagination takes over, with processing power that no machine can match. To play FF7 is to also create FF7 in your mind, hearing what you personally think Cloud sounds like, what the smell of Mako is like, how Aerith’s laugh sounds when she gets the idea to suggest to Cloud that he dress up like a woman.

Abstraction and the role of your imagination in FF7 is perhaps most obvious when exploring the overworld. Cloud’s model towers over tiny buildings, abstractions meant to represent entire towns. We know consciously that this isn’t a simulated reality, it’s an abstracted one. Our minds fill in the gaps with endless detail, directed by the artistic merits of this classic RPG.

AAA video games these days seem to reject this approach, choosing instead to try and create playable spaces as close to real-life scale as possible. But how many of those kinds of games, I wonder, will stand the test of time the way FF7, with its wonky scale and repeated animations, has? With its “weird, ugly, uncomfortable, and nasty” elements, FF7 remains a world beyond what technology can produce alone. What we assign to FF7 has as much value as the data originally printed on those three PSX discs.

The parts that haven’t aged so well

FF7 is far from perfect, of course. While the game mostly sustains a thrilling story of saving the world from a powerful antagonist across 40+ hours, every time I get to the last third of the game’s main narrative, I’m always a little underwhelmed.

That last part, spread out toward the end of the second disc and the entirety of the third, is a series of quests to hunt down key items and opportunities for optional encounters. This home stretch contains far fewer interesting character backstory reveals, such as the truth about Cloud’s mysterious past, Barret’s traumatic loss of his hometown and family, or Red XIII’s relationship with his father. It mostly boils down to encounters with Shinra forces to try and take the awkwardly named “Huge Materia” from them.

FF7’s latter parts could’ve used a few more rewrites, I think. Had Yuffie and Vincent been mandatory members of the party, with their backstories more thoroughly woven in, FF7’s final hours could have been more compelling. The game also could have done more with its temporary shift to Tifa and Cid as main characters while Cloud is off doing his mental gymnastics.

FF7 also has a few other pain points, particularly in 2024. The random encounters are sometimes disruptive to the game’s emotional texture and often too numerous. The absence of auto-save is a frustration. And while I probably wouldn’t wish to see a fast-travel option in this game, some kind of quest journal with a brief summary and indication of where to go would be nice. Yes, you can sometimes figure out what you’re supposed to do by talking to random NPCs, but even in 1997, this process often felt aimless and time-wasting.

Finally, while the ability to individually spec out characters by way of materia sure is cool, managing it across multiple characters can be a serious chore. The amount of characters and options you have available can induce a sense of choice paralysis and uncertainty as to who should fill what roles. Amusingly, the game seems to be aware of this somewhat cumbersome mechanic. Once you regain control of Cloud after playing as Cid for a short while, talking to Cid will result in the following line:

I know how tough it is bein’ a leader, because I’ve been one. I always forget who has what materia.

Final Fantasy VII is a timeless classic

Late in Final Fantasy VII’s story, in an optional narrative beat, Red XIII’s adoptive grandfather Bugenhagen tells him to “look always to the eternal flow of time which is far greater than the span of a human life.” Whether it’s the influence of the two recent remakes or not, I’ve felt compelled to observe when FF7’s characters refer to time, to history, to legacies that characters hope to live up to, and past injustices they seek to right. Final Fantasy VII is a game about many things, but history and how things change is perhaps one of the most important.

Read More: Final Fantasy VII Rebirth: The Kotaku Review

This is a game that has played a key role in the arc of my life thus far, and it’s one I will continue to play in the future. I imagine I’m not alone in this sentiment. The recent remakes sure are fancy modern things which I’ve enjoyed far more than the other FF7 expanded media, but they don’t compare to the timeless essence of Cloud’s first and best saga. Few games do.

Upon replaying this game, I knew I’d once again have emotional responses to Cloud’s search for identity, and his relationships to Tifa and Aerith. I knew Barret’s return home to Corel would hit me again with a sunken sense of sadness for what this man had lost, and the anger and yearning for revenge that Shinra had instilled in him. These interwoven stories of society’s misfits coming together for each other and the world still land with powerful emotional resonance.

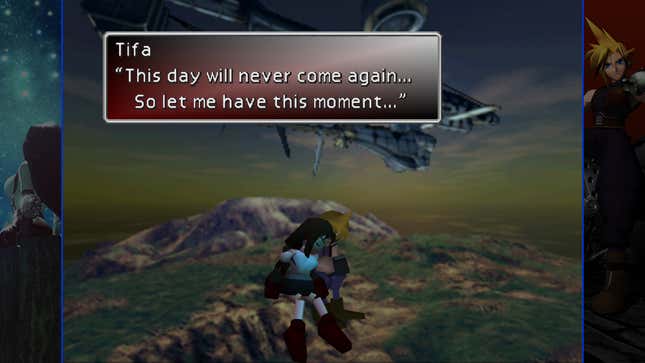

This time around, I also had some new emotions. For the first time, my Gold Saucer date was with Tifa, not Aerith (or, Aeris, as I prefer to keep her original mistranslation for replays). Tifa’s attempt to confess her love for Cloud dovetailed into her commitment to be there for him during his pivotal mental collapse with a narrative impact I wasn’t expecting. It made the proceeding scene between the two of them under the Highwind before the big showdown with Sephiroth land with a sense of love and tenderness that I hadn’t previously felt. It was like seeing this scene again for the very first time, and I came away from this playthrough feeling that I’d gotten to know Tifa more than I knew her before. It’s a lovely illustration of how there are always new depths and new emotional notes still waiting to be discovered in this game as we return to it throughout our lives.

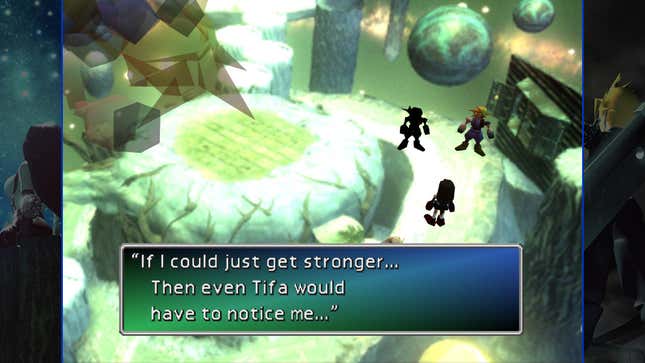

Cloud’s intense moments of self-discovery also took on a new tone for me. After suffering through a dramatic series of events, one which forces him to contend with the reality that so much of his identity is a lie, he turns to face it with a remarkable sense of humanity and truthfulness.

So often, I find that discourse surrounding Cloud’s emotional and psychological journey simply reduces it to part of the game’s science-fiction worldbuilding, to “lore” that explains the connection between Cloud, Sephiroth, and Jenova. But the emotional impact of a heroic character confessing to being afraid of being weak, of being seen as weak, and then choosing to embrace honesty in front of everyone he’s lied to, I think, is the more profound element of FF7’s most dramatic plot twist. And that’s not just me reading into it. Cloud’s speech does involve elements of FF7’s sci-fi, but it starts with an honest confession in which he owns the lies he’s spread:

I never was in SOLDIER. I made up the stories about what happened to me five years ago, about being in SOLDIER. I left my village looking for glory, but never made it in to SOLDIER… I was so ashamed of being so weak; then I heard this story from my friend Zack… And I created an illusion of myself made up of what I had seen in my life…

And I continued to play the charade as if it were true.

Following this, Cloud does mention the “Jenova cells” that were forcibly injected into him, but he makes it clear when he confesses that “my own weakness […] created me.” Yes, the fantasy element of Jenova messing with people’s brains is neat, and it does help amplify Cloud’s mental state, but it’s already working with relatable, human concepts. Cloud’s struggle is one of shame, insecurity, and a bad case of imposter syndrome. And it’s not a magic item that helps him get through this, but a friend. That human connection with Tifa is what grants him the strength to confront his own lies, to own them, not excuse them, and to live without pretending.

That wasn’t all. Though Aerith’s death always layers such an intense cloud of tragedy over the game, so much so that I often find FF7 somewhat depressing to play, this time the sound of children laughing and playing in the game’s final moment brought me tears of happiness and hope, and instead begged me to consider the hopefulness of this game. As I turned off my Switch to return to this reality, one with its own challenges of environmental catastrophe and political violence, with tremendous loss and sadness, I felt a greater urge to not fall into despair.

Final Fantasy VII will always be the same epic fantasy classic, and I will always learn something new from it.