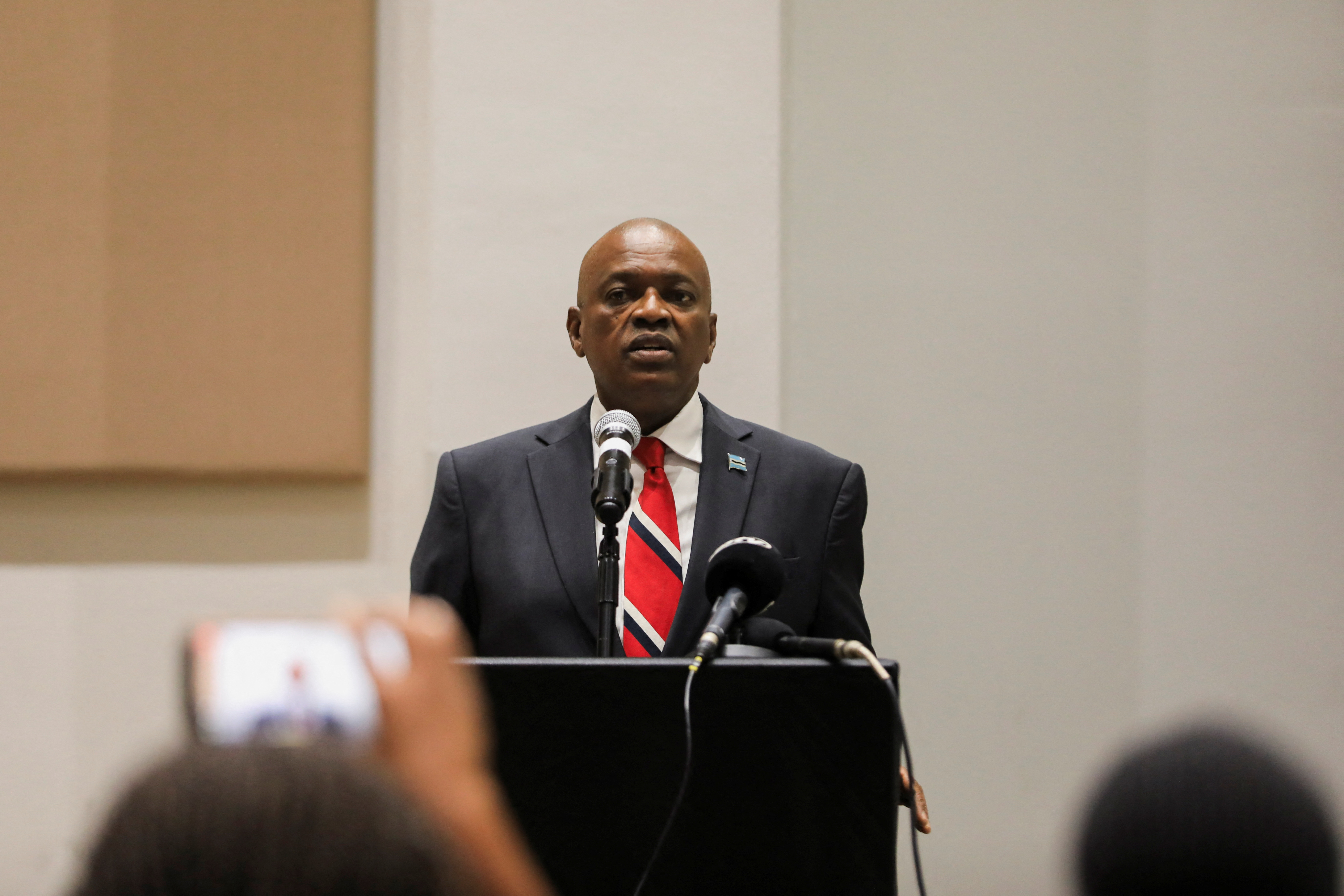

Mokgweetsi Masisi said his party ‘got it wrong big time. I will respectfully step aside and participate in a smooth transition process ahead of inauguration. I am proud of our democratic processes and I respect the will of the people’

Botswana’s elections have always been seen as a model for Africa, but the one last week has a somewhat wider relevance. The way its politicians handled victory and defeat could serve as a model for politicians in the United States.

Botswana has been democratic since it got its independence from Britain in 1966, and for all that time it has been governed by the same party, the Botswana Democratic Party. Now the BDP has finally lost power – and there has been no uproar, no claims and counterclaims, no crisis.

There has been no major political violence in Botswana’s past, nor did the BDP have a history of heroic struggle for independence against evil oppressors. When the British declared that they were leaving the BDP won the first free election, and Sir Seretse Khama, descended from local royalty, was elected president.

He kept getting elected until his death in 1980, and other BDP leaders followed in his wake (including his own son Ian in 2008-2018) all the way down to last Friday. But Botswana remained a democracy and the country prospered thanks to a small population (2.6 million), a large number of high-end tourists, and diamond mines.

In a continent where most governments are bad and most elections are rigged, Botswana has been an island of domestic peace and democratic rule. It has some major advantages, however. Some 80 per cent of its population belongs to the same ethnic group (Tswana), which is rare in Africa. It is also a welfare state, which is even rarer.

Even after 58 years in power, therefore, the BDP’s defeat in last week’s election came as a shock. It was largely due to a high level of joblessness among young people. There’s lots of money sloshing around, but diamond-mining doesn’t create much employment and the young are frustrated even though they are not going hungry.

The BDP’s share of the vote in recent elections has been just above 50 per cent, so its defeat should not have come as a surprise, but few people were old enough to remember a time when it had not been running the country. Despite all the signs, the BDP was psychologically unprepared for defeat.

So what did President Mokgweetsi Masisi do when the votes were counted? He called up Duma Boku, the leader of the victorious Umbrella for Democratic Change (UDC), to congratulate him, of course. That’s what the defeated candidates in an election are expected to do in a democracy.

Afterwards, Masisi confessed to a press conference that his party “got it wrong big time. I will respectfully step aside and participate in a smooth transition process ahead of inauguration. I am proud of our democratic processes and I respect the will of the people.”

“What has happened today takes our democracy to a higher level,” replied Duma Boko. “It now means we’ve seen a successful, peaceful, orderly democratic transition.” That’s how responsible grown-ups behave in a democracy, even if it’s the first time power has changed hands in 58 years.

Why is this a relevant topic for today? Because the United States, far bigger, much richer and with several centuries’ experience of democracy, is holding an election this week, and a significant number of Americans fear that it could lead to a civil war.

I don’t know the outcome of Tuesday’s vote as I write this, but a civil war certainly wouldn’t happen if Donald Trump won the election. There would be great concern that a second term for Trump could greatly damage American democracy and civil rights in particular, but his opponents would realise that violence would just make matters worse.

The bigger risk is an electoral defeat for Trump, because he would be certain to claim it is fraudulent whether he truly believes it or not. Even then a full-scale civil war would be unlikely, but the United States is a heavily armed society where violence is, in H. Rap Brown’s formula, “as American as apple pie.”

Botswana is not that sort of place. Most countries aren’t. But while political issues in the United States are much the same as they are in other developed countries, the ideological passion that Americans bring to them has always been off the scale.

Consider, for example, the issue of slavery. Both the United States and the United Kingdom were deeply in the slave trade for a long time, but when the British finally realised it was wrong they just bought the slave-owners out.

When a majority of Americans reached the same conclusion thirty years later, it set off a civil war that killed at least three-quarters of a million soldiers (about 2 per cent of the population at that time). The policy differences at issue in this election are not very different from those elsewhere, but Americans have whipped themselves into an existential frenzy about them.

Gwynne Dyer’s new book is Intervention Earth: Life-Saving Ideas from the World’s Climate Engineers