Acacia Saligna is pretty and fast growing but it’s an alien causing environmental havoc

To many people, both Cypriot natives and visiting tourists, acacia is synonymous with the landscape of Cyprus. Whether eliciting fond memories of its sweet scent and vibrant yellow flowers, providing a splash of green in an otherwise seemingly mono tonally brown expanse of scrub land, or simply seen as welcome shade under which to escape the glare of the sun, many view the various species of acacia present on the island as benign a part of the environment of Cyprus as the olive or carob. However, herein lies a problem.

There are a little over a thousand different species of what we call acacia found throughout the world which are now split into a number of taxonomic groups, with native ranges for different species found in Australasia, South America and Africa, yet none native to Cyprus. Several species of introduced acacia are now present on the island, however, it is the Australian species Acacia saligna (commonly known as golden wreath wattle or orange wattle) that is by far the most problematic for the environment and economy alike.

First planted by the British during colonial times as a quick growing source of firewood, fodder intended to prevent overgrazing of native species and possibly to aid in draining wetland areas, more recently acacia has been planted ornamentally in gardens, public spaces and along highways as a shade and greening tree, and to reinforce soil and prevent erosion as a quicker growing alternative to native species ecologically better suited for these purposes.

The issue is that Acacia saligna has the ability to grow much more rapidly than native Cypriot species and very quickly outcompetes them for light, water and nutrients. It consumes a huge amount of water intended for agricultural use and both it and the extensive leaf litter it produces are highly flammable and aid the intensity and spread of fire which both have significant economic impacts. This is further compounded by the species releasing biochemicals which negatively influence other organisms (a process known as allelopathy), disrupting the way nutrients are exchanged, rapidly growing from both seed and roots of existing plants, and producing vast amounts of seed which remain in the soil even after the tree has been removed.

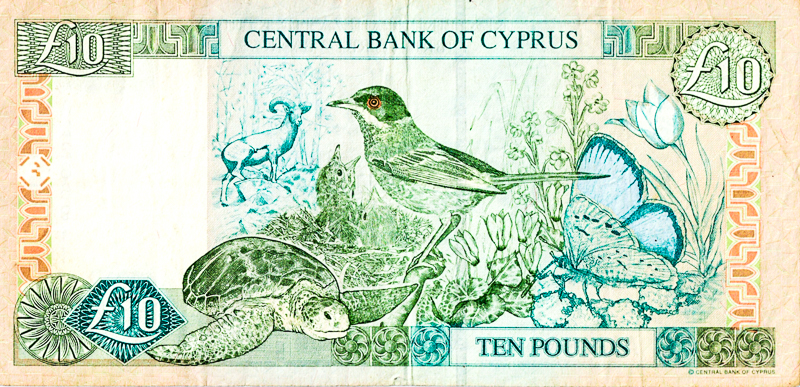

Now found across all parts of the island from sea level up to around 700 metres, acacia has displaced many native species of not only trees, shrubs and other plant life. Also the native animals that over many millennia have evolved very specific habitat requirements in order to survive, now struggle to do so as invasive acacia takes over and these required habitats disappear. This has had a dramatic effect across the entire ecosystem and the number of native at risk species in Cyprus being displaced by acacia is now into the double digits.

Cyprus is not alone in facing these issues and the European Union included Acacia saligna as an Invasive Alien Species (IAS) of union concern in regulation 1143/2014. The restoration of protected areas from invading acacia is an obligation under the Habitats Directive 92/43/EEC and also Cypriot Law 120(I)/2019 which regulates at a national level the implementation of EU IAS regulations, yet while the species is in Cyprus banned in all kinds of plantations it persists, and in some cases is actually planted and irrigated for the use of illegal bird trapping in direct violation of the law. As a result, a number of projects focused on removing this species and returning areas to their native state have been implemented.

Both the environment and forestry departments carry out acacia removal across the island, the British bases have removed tens of acres of acacia, the Darwin Plus funded “Habitat Restoration & Wise Use for Akrotiri & Cape Pyla” project included this action within its objectives, and there are also a number of related projects aimed at creating awareness of the issue being run by a wide range of organisations.

There have of course been objections to the removal of invasive acacia, mainly from those who aren’t aware of the extent of the issues the species causes for both the environment and economy, or feel that there is some form of loss which cannot be replaced. The use of non-invasive and native species to replace acacia is simple, effective and widely beneficial, and any potential issues can and should always be mitigated. In one case for example an environmental organisation objected to acacia removal as it would allow light pollution to reach a nesting site of protected sea turtles which would be highly detrimental to their survival, yet simply screening the lights at source on the beach side or planning some other form of mitigation before removal would have prevented any issues.

While removal of acacia can be difficult, there are useful guidelines published by the forestry department and various methods trialed in other countries such as the use of Epsom salts and Rosemary oil rather than more toxic chemicals hazardous to all forms of life, along with biological control methods using non-invasive fungus and insects, all of which have proven successful.

Benefits of removal are both environmental and economic and include a reduction in the impact of fire on the island which spreads far less rapidly in many native species, an increase in water availability for drinking and agriculture which can reduce costs to consumers, the reduction of sites usable for illegal bird trapping which in some years sees the slaughter of over 1 million birds on the island, and the restoration of native habitats, the wildlife they support and biodiversity in Cyprus as a whole.

Less obvious positives include being able to use the removed acacia directly as wood fuel or converting it to charcoal as opposed to importing this, as green mulch to prevent water evaporation and fix nitrogen, and the reestablishment of native plant and tree species which can be used as raw materials in traditional craft and food products being only a few examples of the environmental and economic benefits that can be realised.

As we transition to more environmentally sound practices across all aspects of life, nature and experience-based tourism is becoming increasingly popular. With around 20 per cent of the economy of Cyprus reliant on tourism and the island being a biodiversity hotspot home to many rare and endemic species of plants and animals, while also having a unique cultural heritage and a need for traditional skills to be preserved (all of which can be leveraged to generate income sustainably), there is a great opportunity waiting to be taken advantage of by those who understand that a rich and balanced environment can be not only a part of economic security, but in fact a key resource used to achieve this, and as such something very much worth taking care of.

Matthew Holloway has over a decade of experience working in the fields of ecology and conservation with a number of NGOs within Cyprus and is currently embarking on post graduate studies in this area