COP29 has completed its first week with some successes, but also with a series of controversies.

France’s top climate official is not going to COP29 in Baku after Azerbaijan’s president, Ilham Aliyev, reacting to criticism for cracking down on dissidents ahead of COP29, accused France of “brutally” suppressing climate change concerns in its overseas territories. He accused both France and the Netherlands for their “neocolonialism”, which he linked to climate change. Both France and the Netherlands categorically reject this.

On Tuesday Argentina’s president, Javier Millei, also pulled out the country’s delegation, saying they will not participate in the negotiations. This is interpreted as an indication that he will follow Donald Trump, whom he met earlier in the week, if and when he pulls the US out of the Paris Climate Agreement. Like Trump, he previously called global warming a hoax.

In another controversy, Aliyev defended his country’s plans to continue expanding production of oil and gas, saying these are a “gift of God”. He criticised what he called double standards from Western nations “for lecturing countries on climate change while remaining major consumers and producers of fossil fuels”.

With many world leaders skipping it, so far COP29 has been marked more by division than unity, and of course Donald Trump’s re-election has cast a big shadow, but there have been areas of progress.

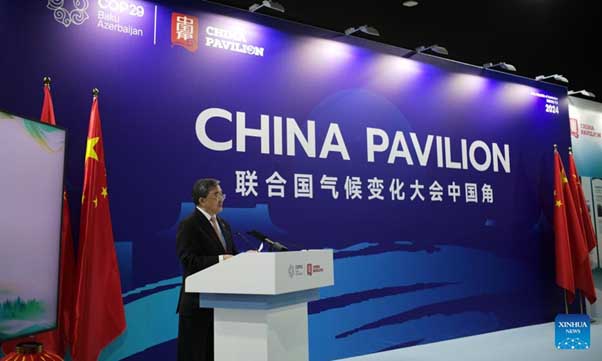

China taking advantage

Seizing the moment, and responding to the uncertainties surrounding the US, China is making its presence felt, even though its president Xi Jinping is not attending. It sent close to 1000 delegates to Baku, where it is showcasing its determination to accelerate its energy transition, sending a message that it is ready to fill the “climate leadership vacuum”.

Earlier in the week it co-hosted a summit on methane with the US. Chinese climate envoy Liu Zhenmin said that this “cooperation on global climate action will continue to be enhanced.”

Not to be left behind, the EU also launched a new ‘Methane Abatement Partnership Roadmap’ to accelerate the reduction of methane emissions associated with fossil energy production and consumption.

China is also taking the responsibility of “pushing forward green and low-carbon development”, stating that it is “very willing to cooperate…to promote a low-carbon and sustainable future”. China also confirmed that it is “willing to take a more active role in global climate governance”.

Climate finance

It is estimated that climate finance to help developing countries would need to rise to $1.3 trillion per year by 2035. The success of COP29 hinges on whether countries can agree a new New Collective Quantified Goal on Climate Finance (NCQG) and who will contribute to it. Trump’s election has put the US future role in this in doubt.

China and the G77 group have rejected a first draft of the climate finance text. China and the Gulf States have been classified as developing economies and are exempt from contributing. However, according to the EU and other developed countries, that must change if the overall amount of funding is to be increased. They are asking China, India, Indonesia, Brazil and South Africa to pay for their own mitigation, adaptation, loss and damage. But these countries are resisting this, and in doing so they have the support of the Brics countries and Africa.

India and other Brics members are cooperating as an informal bloc at COP29 to resist the Western pushback on financial support for developing countries. They are putting pressure on Western countries to pay reparations for past pollution from their growth.

India said that developed countries had polluted the planet for their economic growth, but are now using the excuse of a polluted planet to force developing countries to pay a high cost for their growth.

However, there were signs of movement. A few countries and multi-lateral banks made climate finance commitments that could increase to about $165 billion per year by 2030. Even though this is low in comparison to what is needed, it could build up as COP29 progresses and in future COPs.

China also said that it has already “provided and mobilised project funds of more than $24.5bn for developing countries’ climate response”, giving it grounds to push developed countries to do more.

New standards were agreed on Monday that clear the way for the creation of a UN carbon market set out in Article 6 of the Paris Agreement.

This defines how countries can voluntarily use carbon credits to meet the climate targets set out in their nationally determined contributions.

There are two main mechanisms for such trading to take place. Under Article 6.2 countries can set up carbon trading arrangements bilaterally, and Article 6.4 outlines a system where trading would happen through a UN-backed carbon market, open also to business.

Calls for reform

Unhappy with some of the developments in Baku, on Friday a group of top climate advocates, scientists and former UN chiefs, led by former UN climate chief Christiana Figueres and former UN Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon, called for reform, arguing that countries expanding oil and gas should not be able to hold the COP presidencies.

But as EU climate chief Wopke Hoekstra said, “Regardless of any disagreements, the COP should be a place where all parties feel at liberty to come and negotiate on climate action.” The UN also confirmed “the principle of every nation should have a right to be heard”.

Many leaders think progress is more likely at COP30, which will be held in Brazil in November 2025.

Dr Charles Ellinas, @CharlesEllinas, is a councilor at the Atlantic Council